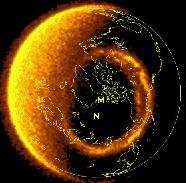

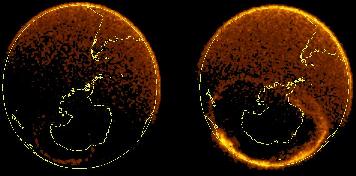

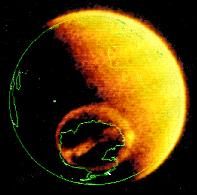

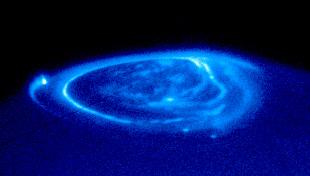

An aurora is the name given to the light that is produced in the upper atmosphere when electrons and protons precipitate from the Earth's magnetosphere down into the lower regions of the upper atmosphere. This precipitation typically takes place along a ring which encircles the polar regions. Aurorae around the north pole are termed Aurora Borealis or Northern Lights, and around the south pole are termed Aurora Australis or Southern Lights.

Green aurora over Hobart, Tasmania in August 2005

Image from Dallas and Beth Stott

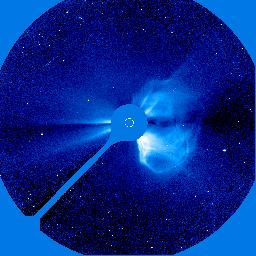

Particles in the magnetosphere typically originate from the sun via the solar wind. Some of these particles precipitate into the lower atmosphere continuously, and the aurorae are thus normally present at all times, although they may not always be visible (due to limited intensity and the obscuring effect of daylight). At times of injection of large numbers of particles from the solar wind (following solar activity) the aurora become brighter and the ring region in which they occur (termed the auroral oval) expands and moves closer to the equator.

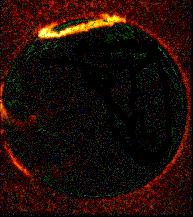

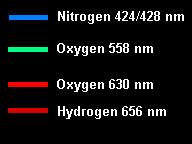

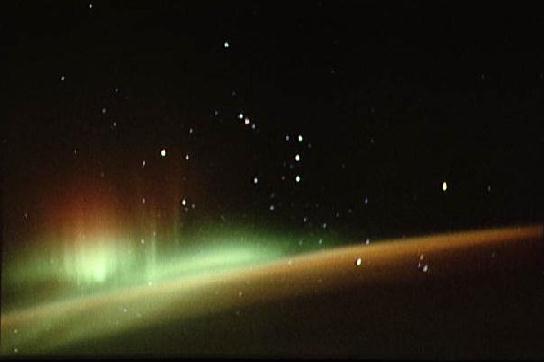

When these particles strike molecules of air at heights from 70 to 600 km they produce various colours of light that may be seen from the ground and from space. The process is similar to what happens inside a TV tube when electrons are accelerated toward the screen. When they hit the phosphor coating, coloured light is emitted.

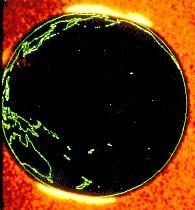

Aurorae take many different forms which follow the patterns and variations of the Earth's magnetic field.

This image taken from the Space Shuttle shows the Aurora Australis glowing above the Earth's surface below the star constellation of Orion. [NASA image / STS-59]